I was talking with someone who was stunned, happy and a little nervous that a competitor had recently raised private equity at nearly a $100 million pre-money valuation. It would be natural to try to value one’s own business based on the valuation of a competitor that was reported in the press.

Don’t believe the hype. Here is why: the valuation that private equity or venture investors use to determine their share of the equity of a company in an investment scenario is almost never the same valuation that they would have used in a liquidity scenario. Importantly, although headline-grabbing valuations are often reported to the press, the underlying terms of an investment are almost never reported.

First, lets clarify some terms:

- Investment scenario – current investors of the business largely remain invested and new capital is invested into the company.

- Liquidity scenario – current investors of the business sell their shares in the company.

- Pre-money value – the valuation of the company used to determine the ownership percentage of the new investors. For example, a $10m investment into a company with a $100m pre-money value would give the new investors a 9.1% ownership of the new company calculated as 10 / (100+10).

Companies that raise outside capital have many incentives to raise capital at a headline-grabbing valuation including: enhancing their credibility among potential customers, partners and employees; pricing stock options for new employees at a less-dilutive value; and attempting to set a floor for any acquisition pricing discussions. Investors, on the other hand, are often happy to oblige the valuation desires of the management teams so long as they set the other key economic terms of the deal. There is an old saying among snarky investors: your price, my terms.

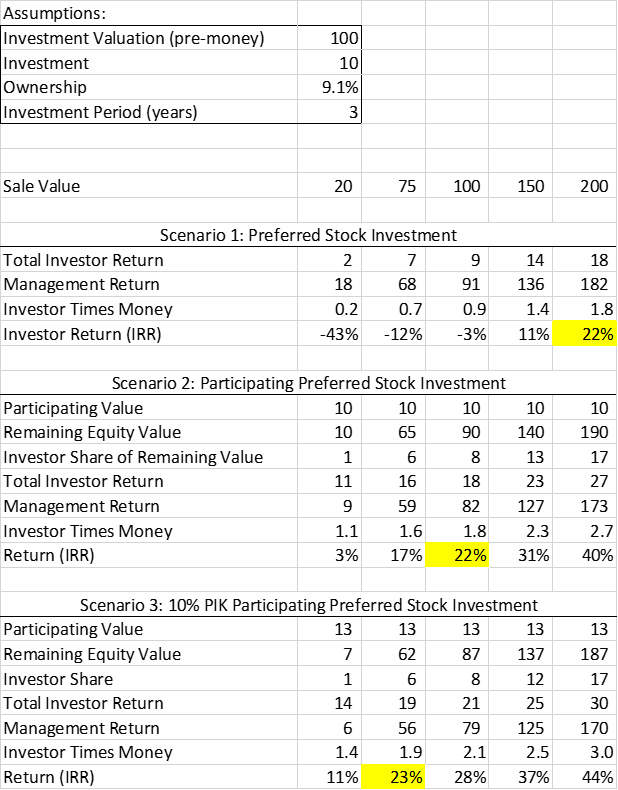

As an example, let’s assume that a company raises $10m from investors at a $100m valuation and that they are invested in that company for 3 years before it is sold. We will look at 5 different sale prices ranging from $20m to $200m and 3 different sets of terms (preferred stock, participating preferred stock and PIK participating preferred stock).

In scenario 1 above, by owning 9.1% of the company, the investors would receive $18m of the proceeds yielding a 22% return if the company was ultimately sold for $200m. However, in scenario 2, by changing the terms slightly to a participating preferred, the investors generate the same return by selling the company for only $100m. Scenario 3 demonstrates that PIK participating preferred stock enables the investors to yield the same result with only a $75m ultimate sale value. Note that in each scenario, as the investors do better, the management team does worse.

Investors are fully aware that the pre-money valuations of companies that they invest in are often greater than the true market value of those businesses. However, they make their returns with the terms of the deal. Just don’t believe the headline-grabbing valuation is an independent market valuation of those businesses.

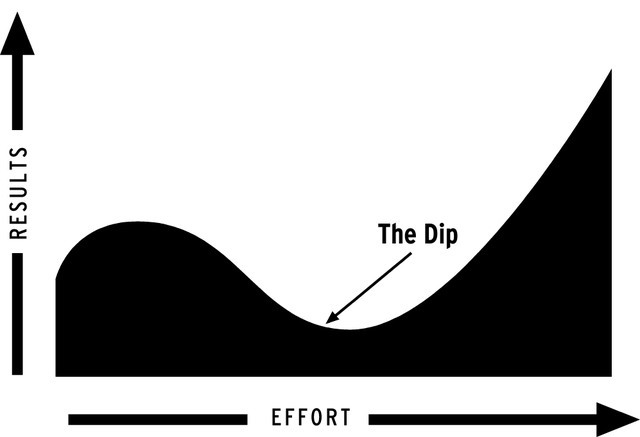

Sometimes there is no upward slope after the Dip (aka the abyss). Those are situations when the smart answer is to quit. Yes, knowing when to quit and when to persevere is a critical distinction. But be careful: the Dip is your friend. For most of us, the Dip is our only real barrier to entry from a string of would-be competitors. The Dip weeds out those that can’t make it.

Sometimes there is no upward slope after the Dip (aka the abyss). Those are situations when the smart answer is to quit. Yes, knowing when to quit and when to persevere is a critical distinction. But be careful: the Dip is your friend. For most of us, the Dip is our only real barrier to entry from a string of would-be competitors. The Dip weeds out those that can’t make it.